Standards, The NMRA, and Japanese Trains

29 June 2012 01:37 Filed in: Model Trains,Standards

I recently renewed my NMRA membership, and that set me to thinking about their role in standards-setting, and what it means for the hobby, and about the application of standards to the Japanese-prototype Model Railroading I do today. I’ve been an NMRA member for 20+ years, and the reason I originally joined was to get access to their standards, back when that meant buying a three-ring binder full of paper. Today, those Standards and Recommended Practices are available online, free for anyone to download (the Data Sheets are still members-only, but those are less critical although full of useful information), and I think that’s one of the best things they’ve ever done, even if it does give people one less reason to join.

Membership isn’t required for anyone (unless you want to buy things from them, access their reference library, or take advantage of other benefits), and it may not be all that useful for many, particularly if you have no interest in club activities (I go to their local shows, but I’ve never been to any meetings). And it’s pricy, with a minimum cost (without magazine) of US$44 per year (US$32 for students under 25 with a school ID). On the other hand, if you can afford it, it’s a great way to support their standards-making activity. And while they’ve fumbled a few things (DCC transponding/RailCom is my current pet peeve), on the whole they have a 77-year record of being useful to the hobby. So consider joining the NMRA if you can afford it, for that reason if none other. Although primarily a North American organization, they have “regions” serving Australasia, Britain, Canada, the Atlantic region, and a sister organization in the Netherlands.

The NMRA isn’t the only Model Railroading standards body, of course. In Europe, MOROP provides standards in French and German. In existence since 1954, today it works closely with the NMRA to ensure both organizations have compatible standards. The standard DCC “NEM” socket widely used by European manufacturers derives from a MOROP standard; NEM stands for Normes Européennes de Modélisme (or “European Standards for Model” per Google Translate). There are also many standards that have been developed by clubs and made their way into more general use, such as the N-Trak modular standards. My Links of Interest page has links to a number of independent standards of potential interest.

Now lets talk about how this affects Japanese models. Of course, Japanese N-scale uses “standard” track and switches, so you can use anyone’s track (even that of European manufacturers like PECO or North American ones like Micro Engineering). But is it really “standard”? The basic track standard derives from the original N-scale manufacturer Arnold (of Nürnberg, Germany) and Trix, another early manufacturer. Both NMRA (S-1.2 & S-3.2) and MOROP (NEM 122) have track standards for N-scale based on that. The NMRA’s S-3.2 specifies the “gage” (space between rails) as 9.02mm +0.10/-0.05 (there’s a wider range in S-1.2), while MOROP specifies it as 9mm without stating an allowed variation. While it might seem a bit odd that they don’t exactly match, what matters is that they be close enough in agreement that equipment built to one will work reliably with equipment built to the other.

Note: “gauge” is the usual spelling for the distance between rails (and a number of other “distance between” measures, and for tools used to measure things. However “gage” is a U.S. English variant. The NMRA standards use “gage”, but I typically use “gauge”, particularly with regard to rail spacing (where it seems fairly commonly used, even in the U.S.). So the different spellings in this post are intentional, really.

But standards are only a guide, and manufactures make decisions based on what their customers want, which in the case of track is problem-free operation. This can lead to standards being deliberately ignored. According to Wikipedia, N-scale track tends to vary from the standards, although other standards are more closely followed. I’m not sure what they mean by that, and it may simply be a comment that N-scale track isn’t exactly 9mm apart. As we’ll see, that’s actually still in agreement with the NMRA version of the standard.

Measuring gauge on some of my N-scale track, while I found numerous examples outside the NMRA’s strictest requirement (from S-3.2) of 8.97mm to 9.12mm, I found none outside the more lenient 8.37mm to 9.32mm range defined in S-1.2 for general track. In fact most of the Unitrack was around 9.1mm to 9.2mm (but ranged from 8.59mm to 9.30mm), several Tomix Finetrack samples were around 9.14mm, but one was 9.02mm, some MicroEngineering track was between 8.97mm and 9.20mm, and one twenty-year-old piece of Atlas track I had was 9.27mm. This suggests that N-scale track is purposely built slightly on the wide side, to accommodate out-of-spec wheelsets, but within the range allowed by the standard, and that there is a fair amount of manufacturing variation even within one product line.

Note: track gauge in curves needs to be wider (and there are standards for that, too), but all of the above was straight track.

My NMRA standards gage (more on this later) will, in fact, pass as correct track with a spacing up to 9.27mm. Out of about a dozen sections of track I measured, only one fell outside this maximum, and that just barely.

There are standards for dozens, if not hundreds of dimensions relevant to N-scale track, wheels, couplers and other things. These serve as a guide, and give manufacturers a point of reference. They may make track wider because many wheelsets are out-of-gauge, but they do so knowing that the standard width of a wheel will still work across the wider-but-allowed gap, at least for most trains, thanks to those very standards. There are groups following “finescale” standards that have less tolerance, and assume models built to “finescale” also, but that’s a very different thing from the general-use standards followed by most manufacturers.

But that’s taken us a bit away from Japanese N-scale, so let’s go back there. When building a model railroad, one very important question is around how far apart trains need to be from each other and from potential trackside obstacles. For the former, when working with sectional track the answer is given to you be the manufacturer. Normal Unitrack has a minimum 33mm spacing between parallel tracks, and in fact Kato’s blue rerailer tool (available in several of their track sets) has three pairs of notches on one side, allowing you to ensure 33mm spacing for three parallel tracks. Unfortunately it’s not always easy to create that spacing with Unitrack (see the PDFs on this page for some information on how to do it). Tomix Finetrack uses a different spacing (37mm) and Kato Unitram track uses yet another (25mm).

Note: the outer spacing on the rerailer (66mm) is also the standard spacing for tracks on two sides of an island platform.

The NMRA standard MS-1.0 defines the minimum spacing for parallel track on a module as 1.5” (38.1mm), so you can see that Japanese trains diverge from the standard here. That’s in part because the trains are smaller, built to 1:150 scale for the most part, rather than 1:160 scale. Typical hand size, or rather finger diameter, may also play a role, since part of the reason is to allow trains to be picked up without disturbing adjacent ones.

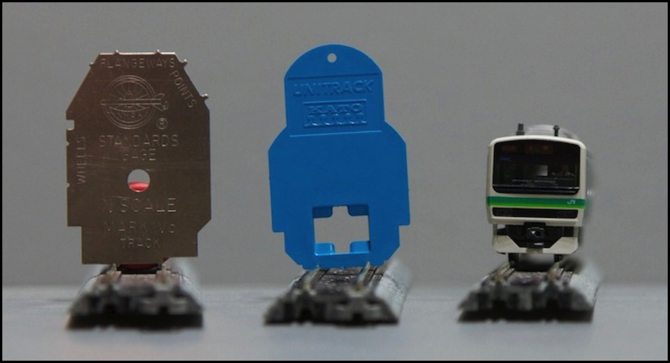

The other part of clearance, avoiding trackside obstacles, is illustrated in the photo at the top of the page. This shows a metal NMRA “clearance gage” (conforming to standard S-7) next to a blue plastic Kato clearance gauge and a Kato 1:150 scale commuter E231. Note how wide the NMRA gauge is compared to the Kato gauge. The NMRA gauge is 29mm wide and 42mm railhead to top. The Kato gauge is just under 28mm wide, and 44mm railhead to top, but substantially narrower (20mm) just 29mm above the rail. This provides clearance above the center of the car for pantographs (or smokestacks) but conforms to the lower body height of Japanese trains (the NMRA gauge has to clear modern double-stack container cars and similar).

Although the Kato gauge has notches on the bottom, these aren’t for validating rail spacing as they only fit track roughly 9.27mm apart. Instead they clip onto the track, the plastic deforming to grab the rails snugly, allowing the gauge to be set up and left in place while positioning track or structures. It can also be used to measure the minimum clearance between side platforms on single track (23mm, or 11.5mm to track center; surprisingly the same platform clearance provided by the NMRA gauge) and, when clipped to Unitrack, platform upper surface height (14mm from “ground” surface).

The Kato gauge comes in several of their sets, but can also be bought with a Terminal Unijoiner pair (part 20-818) for US$5 list. I have a number of these, and they were very handy for checking clearances as I was planning the subway tunnels and elevated station (although in some cases I cheated a little after measuring actual pantograph heights).

The NMRA gauge has a number of interesting notches and tabs, for measuring a variety of things (e.g., wheel flange spacing, wheel width, guardrail placement, etc), described in Recommended Practice RP-2 and standards S-3, S-4 and S-7. It is available to non-members for US$12 from their online store.

If you want to build a model railroad suitable for all trains, following the NMRA (or MOROP) standards more closely is a good idea. But if your goal, like mine, is a Japanese-prototype model railroad, then there are places where clearances can be closer, and this may provide a better appearance with the smaller Japanese models. But without those standards, it’s quite possible Kato and Tomix both would have created proprietary (and non-compatible) model train systems, perhaps loosely based on the original Arnold designs. We shouldn’t take all the interoperability we have today for granted. Generations of modelers (and that’s who staff those standards-making activities) labored to give us that, and we should all be thankful that they did.